The AI Jobpocalypse: What My Roomba Taught Me

While Silicon Valley preaches the end of human labor, I'm still nudging my Roomba so it doesn't choke on a sock.

For months (maybe years now), the various snake oil sellers of AI have been trying to convince us of the impending labor apocalypse. The argument is that algorithms and AI agents will soon surpass us in all intellectual tasks, so any company will – supposedly – be able to automate entire (human) workflows simply by investing in capital (machines and algorithms). Conveniently, the people saying this are precisely the ones selling those machines and algorithms:

AI could eliminate half of all entry-level white-collar jobs and raise unemployment to 20% by 2030

— Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic (source)

It's the market, amigo!

Some have already rolled up their sleeves to lead by example: last July (2025), Microsoft laid off 4% of its workforce (9,000 employees), arguing that "new AI tools were making some jobs redundant" (Satya Nadella, CEO of Microsoft). The layoffs hit their Gaming division (Candy Crush, Xbox, Activision) and certain marketing and sales departments, but the biggest blow – 6,000 of the 9,000 layoffs – went to engineering and product development teams: from Hololens and Azure Edge to, ironically, their Applied AI unit. One notable case is Gabriela Queiroz, former Director of AI for Startups at Microsoft, a renowned figure in the field, who – against all odds – was also laid off. I'd love to meet the AI agent they put in her place.

The reality is that the layoffs associated with "automation" amount to just a few dozen cases. Most respond to other logics: revenue decline (Gaming), strategic cuts (Hololens), or an increasingly clear outsourcing of the AI business. Microsoft no longer wants to be the lab that experiments; it wants to be the one that packages, bills, and scales. The company has fully embraced its role as a utility: it no longer aims to transform anything, but to monetize its infrastructure (datacenters, APIs, …) like a telco or an electric company. Of course, explained this way, the downsizing doesn't sound so sexy anymore. Basically, they've ditched innovation to focus on product management and marketing.

The IBM case is also well known: at the end of 2023, they laid off 1.5% of their staff and froze 7,800 hires. Arvind Krishna himself (the CEO) even claimed that 30% of their workers were replaceable by AI systems. The truth is they were facing a more than 70% drop in profits due to an extraordinary $5.9B expense from transferring 100,000 pension plans. Today, they claim their AI-first strategy has saved them over $3B, but the number of jobs and hiring rate have already surpassed those of two years ago. In other words, they may have saved money, but they have more workers than before (not fewer).

Other cases like Duolingo or Klarna show that the path to automation is not as straightforward as they thought. Some companies that strongly bet on replacing people with AI have ended up backtracking for reputational reasons, user experience problems, or simply because the results weren't up to the PowerPoint.

There was a time, up until the 1970s more or less, when companies that laid off workers en masse were seen as poorly managed, on the brink of collapse, or unable to adapt. It was believed that getting rid of hundreds or thousands of experienced workers meant giving up their productive advantage; it was like selling the cow to buy milk!

In the 80s, lean management and "shareholder value" came along, and the idea spread that "restructuring" equals "optimizing", and Wall Street started rewarding with stock surges the companies that fired the most and the best. From then on, those that didn't lay off were considered "stagnant", "too slow", or "unambitious". Today, Big Tech has normalized the "hire fast, fire faster" model, and even in high-profit contexts they execute mass layoffs simply to "please the market" – as if it were a Mayan sacrifice.

The Data

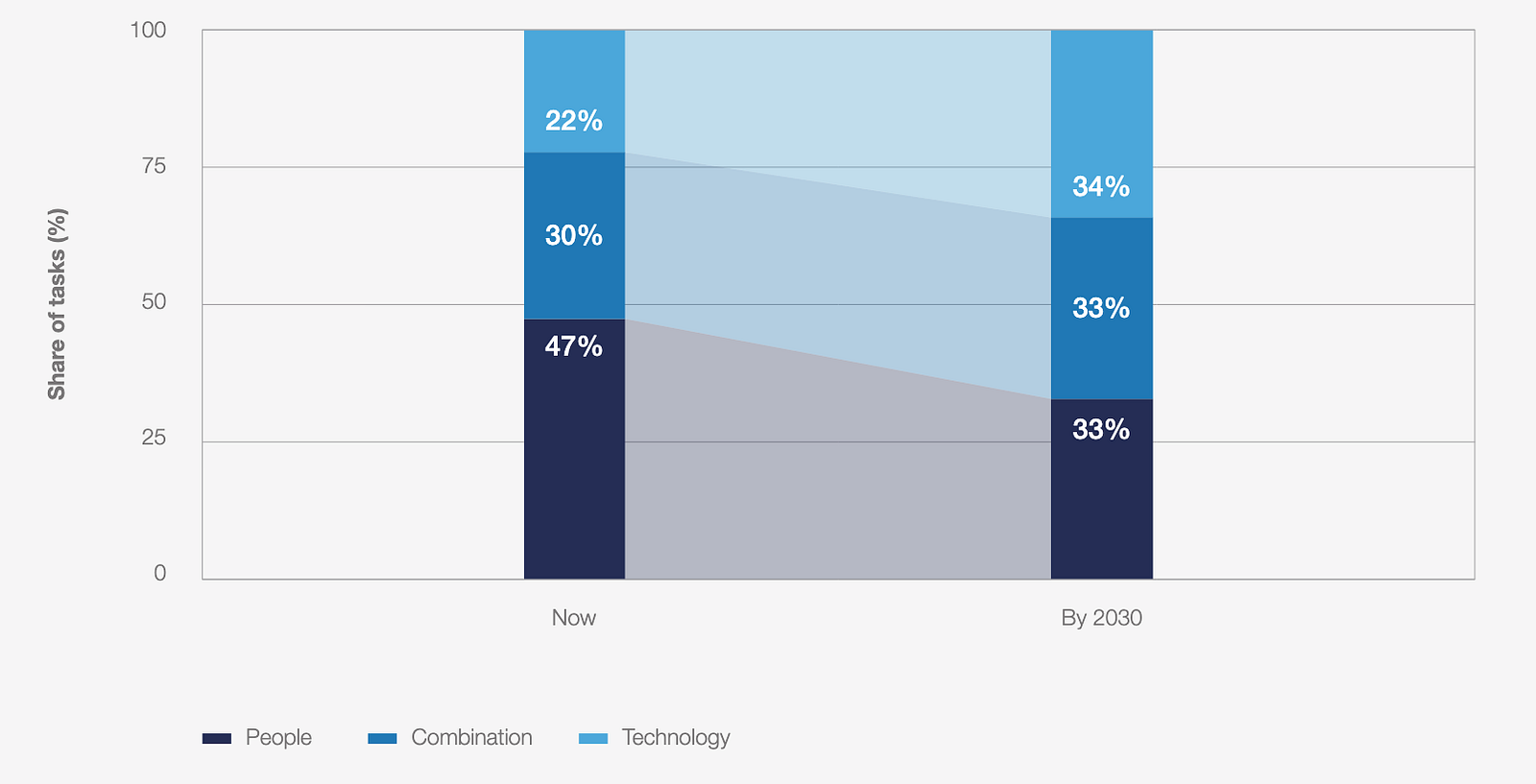

Five years ago, in the Future of Jobs Survey (2020, WEF), various industry leaders predicted that nearly half of their companies' tasks and operations (47%) would be automated by 2023. In the 2023 report, the reality was much more modest: only 34% had actually been automated — barely one percentage point more than in 2020. But in the most recent report (2025) was even more surprising: the WEF estimated that only 22% of tasks are currently automated… Wait, what? Are we going backwards?

Well, it turns out previous reports included a large gray area between "automated tasks" and "human tasks," which covered tasks assisted or accelerated by technology. Hybrid tasks. This year, they opted for a bit more precision, and the snapshot looks like this:

- 22% of tasks are fully automated

- 47% are performed by humans

- 30% are done in human-algorithm collaboration. Ehm… basically, people operating machines.

We haven't seen many headlines claiming that automation has dropped 12% since 2020. And fair enough — that would likely be a misleading conclusion. What's really changing is not so much who executes the task (machine vs. human), but the nature of the task itself. These are different tasks, aimed at delivering faster or higher-quality results — like the difference between writing a report by hand and doing it in Word or PowerPoint.

The WEF's new estimate for 2030 is that 34% of tasks will be fully automated. We'll see.

Fuente: World Economic Forum, Future of Jobs Survey 2024

Another common talking point among AI industry leaders is the idea that, unlike previous technological revolutions, this one is coming for intellectual jobs—not manual ones:

By 2025 we'll have AI that can do the work of a mid-level engineer.

— Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Meta (source)

Writers, accountants, architects, and even software engineers will be deeply impacted by AI.

— Sundar Pichai, CEO of Google (source)

The jobs most susceptible are those of people whose task is to handle information and solve structured problems—like writing code.

— Jensen Huang, CEO of Nvidia (source)

These people say such things while simultaneously biting each other's throats off to hire the very tech talent they claim they'll soon replace. For example:

- Google has opened over 28,000 new software development positions in the last year, mainly in India (source)

- Meta is offering signing bonuses of up to $100 million to lure top AI talent (source)

Sometimes, they don't even seem sure whether their employees are replaceable—or just need to work more hours:

In my experience, 60 hours a week is the productivity sweet spot.

— Sergey Brin, Co-founder of Google (source)

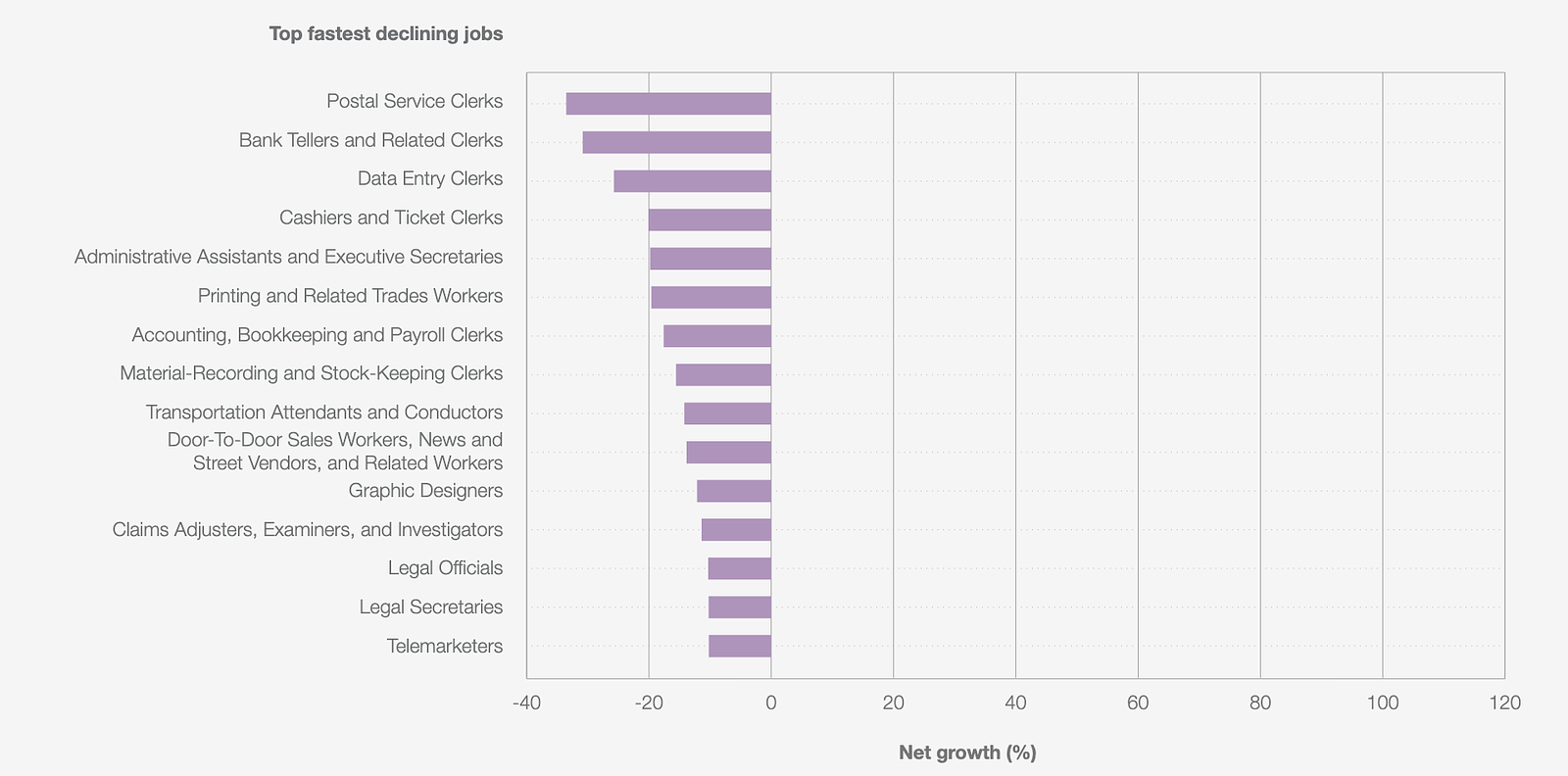

The truth? The roles most affected by technological change are still the routine, administrative ones.Secretaries, delivery workers, data entry clerks, and cashiers are the ones already in decline.

Fuente: World Economic Forum, Future of Jobs Survey 2024

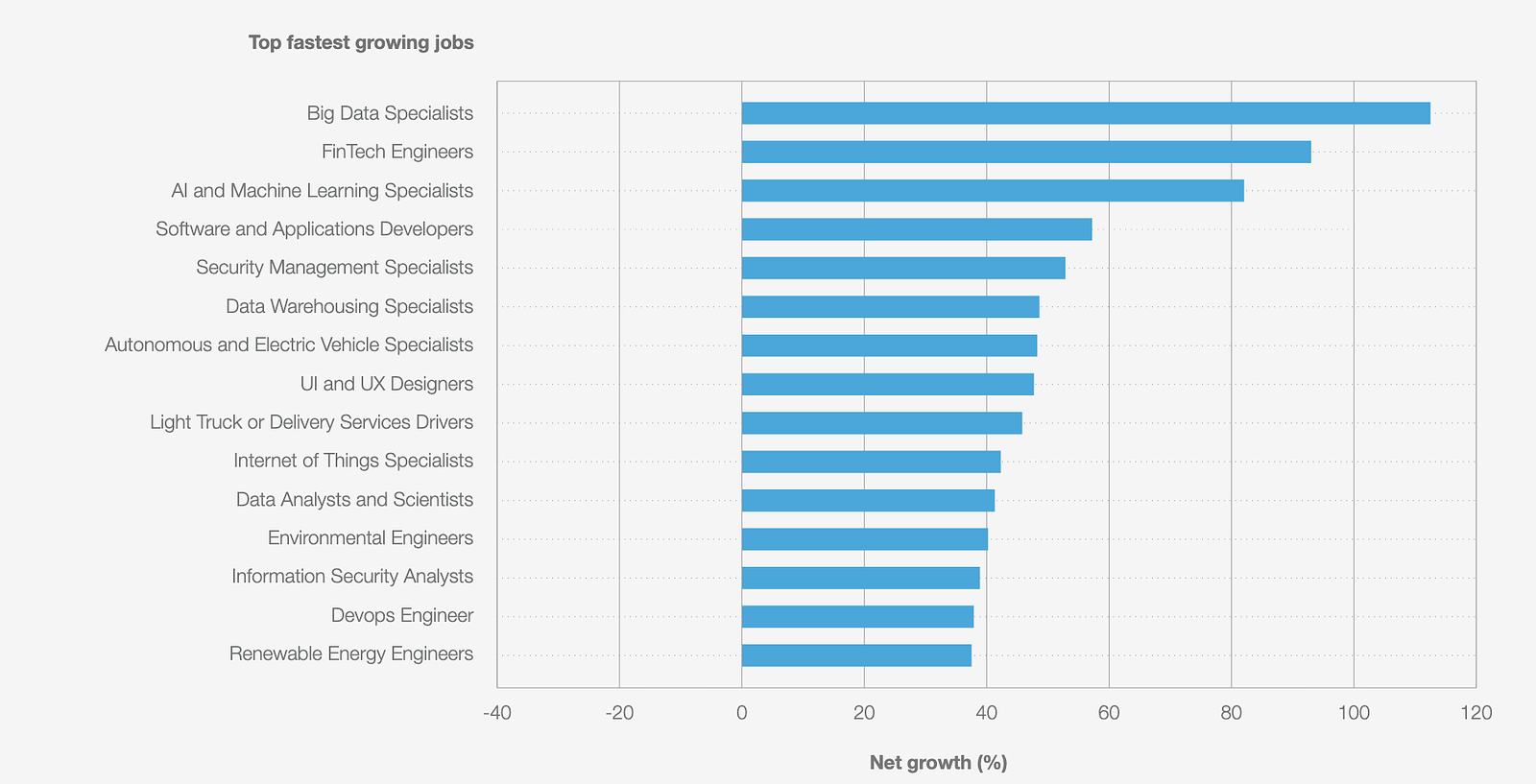

In contrast, there's been a notable rise in demand for tech, digital, and creative occupations. AI and machine learning specialists top the list of fastest-growing roles, followed by data analysts and business intelligence experts, cybersecurity professionals, environmental sustainability specialists, and, more broadly, most professions tied to renewable energy.

Fuente: World Economic Forum, Future of Jobs Survey 2024

For example, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (source) projects that in the next 7 to 8 years, the US alone will need:

- Over 300,000 additional software developers beyond today's workforce

- More than 180,000 new engineers and architects

- And 54,000 new financial assistants

Employment projections in US

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Projections program.

NEM = National Employment Matrix.

2023 NEM occupation title | Employment 2023 | Estimation 2033 | Var %

------------------------------ | --------------- | --------------- | --------

All occupations | 167.849.800 | 174.589.000 | +4.0%

Computer occupations (total) | 5.021.800 | 5.608.500 | +11.7%

- Database administrators | 805.000 | 871.000 | +8.2%

- Database architects | 614.000 | 680.000 | +10.8%

- Software developers | 1.692.100 | 1.995.700 | +17.9%

Legal occupations (total) | 1.394.400 | 1.446.200 | +3.7%

- Lawyers | 859.000 | 903.300 | +5.2%

- Paralegals & legal assist. | 366.200| 370.500 | +1.2%

Financial occupations (total) | 10.977.200 | 11.738.500 | +6.9%

- Budget analysts | 50.800 | 52.700 | +3.9%

- Credit analysts | 73.700 | 70.800 | -3.9%

- Investments analysts | 347.400 | 380.500 | +9.5%

- Personal fin. Advisors | 321.000 | 375.900 | +17.1%

- Claims investigators | 345.200 | 330.000 | -4.4%

- Insurance appraisers | 10.500 | 9.500 | -9.2%

Arch & engineering (total) | 2.639.700 | 2.819.700 | +6.8%

- Aerospace engineers | 68.900 | 73.000 | +6.0%

- Civil engineers | 341.800 | 363.900 | +6.5%

- Electrical engineers | 189.100 | 206.300 | +9.1%

- Electronics engineers | 98.700 | 107.600 | +9.1%

Note: the occupations included in the table are likely to be affected

by artificial intelligence, but they are not intended as an exhaustive

list of occupations susceptible to such impacts.

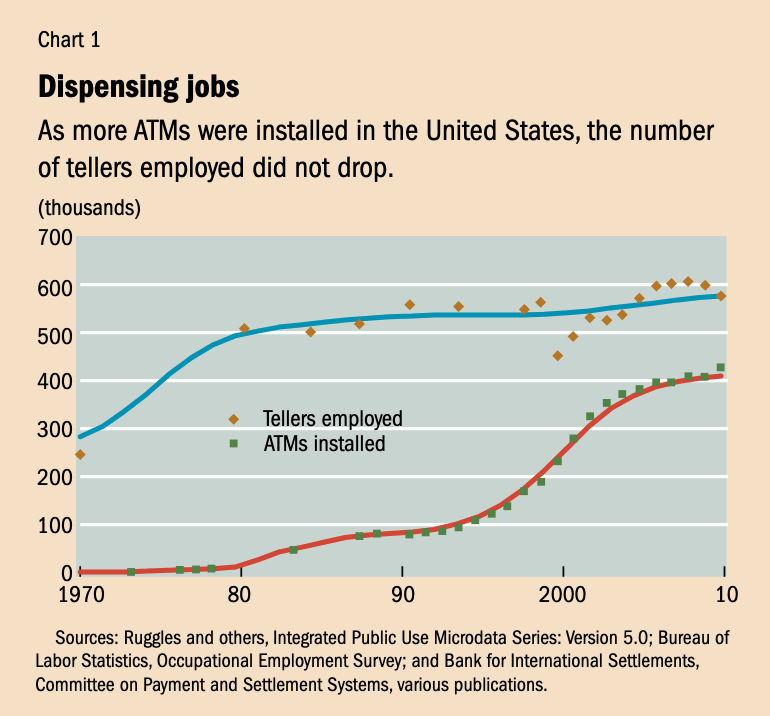

In 2015, economist James Bessen was already questioning the idea of a job apocalypse, arguing that automation doesn't eliminate human work, but rather shifts its value—from task execution to customer experience. For instance, he explained how the rollout of ATMs since the 1970s didn't reduce the number of bank employees, but reshaped their role: less cash handling, more relationship banking and financial advice.

So, does technological disruption have no impact on employment? It does—but not so much in the number of jobs, as in the wage structure. Bessen uses the example of graphic designers. They used to work almost exclusively for print media. With the rise of the internet and smartphones, nearly every company in every industry suddenly needed (web) designers. But:

- Design schools couldn't keep up with the demand,

- Employers were reluctant to invest in training for high-turnover roles,

- The tech was still too immature to justify big investments from schools or companies.

The result? A small group of adaptable, self-taught designers became a highly paid elite, raking in six-figure salaries—while the rest saw their wages stagnate for decades.

This pattern —a hyper-paid elite and a long tail of flatlining wages— has been repeated in almost every white-collar profession affected by automation.Today, we see a mass of developers watching their salaries nosedive, while Mark Zuckerberg hands out $100 million signing bonuses to a tiny tribe of baby-faced engineers who've spent the last five years messing with Transformers.

Lessons from my Roomba

I've had pets all my life—dogs, cats—so I'm pretty used to seeing hairballs rolling across the living room like tumbleweeds in a Western. About six years ago, a colleague recommended I get a robot vacuum. Honestly? It changed my life: now I vacuum several times a day just by tapping a button on my phone. My house is feels way cleaner, and it seems like I spend half the time cleaning.

Last weekend, while I followed the little robot around—moving chairs and untangling cables—I started wondering if this is the real promise of automation from AI agents (and the robots yet to come). Sure, I barely touch a broom anymore. But:

- I still have to prep the floor for it,

- clean it after each use,

- maintain it (rollers, sensors, etc.),

- and accept that the corners are worse than before.

Back when I used a broom, I'd break my back sweeping under the sofa, into corners, behind doors, under the bed… and I'd pay less attention to the center of the room. The robot does the opposite: super efficient with the easy stuff, but useless with the tricky bits. The result? The floor looks clean… unless you check under the table.

And that, to me, feels like the near future of AI. Will it eliminate entire sectors of work? Not exactly. I'm still cleaning—just differently. Will it make life easier? Yes, but rarely without human oversight. Most systems will still need an adult in the room: planning, supervising, and handling the messy corners.

Recently, Micha Kaufman, CEO of Fiverr, posted (source):

So here is the unpleasant truth: AI is coming for your jobs. Heck, it's coming for my job too. This is a wake-up call.

Here's my two cents: I don't think AI came to take our jobs. I think it came asking for our help doing its job. Still… better team up, or you risk getting stuck in the long tail of low wages.

Your turn.